For a while I believed that the gayness of the emo1 scene was just the kind of fandom lore that does not get written down in any official sources and instead must be scraped off the musty walls of LiveJournal and Tumblr. I’m also probably the most un-fun fun person out there, so I do a lot of browsing on Google Scholar in my free time. And you’d be surprised what kind of research exists out there. I swear I hate to pigeonhole myself into being ‘the emo cultural analyst’2 but what can you exactly do when all you care about is emo and cultural analysis?

This is a long-winded way to say that, from what is already out there, I believe I can (very unseriously) contribute to the cultural research of emo, especially as it pertains to the presentations and representations of sexuality. Bisexuality specifically. To aid my discussion, I’ll employ as my object one of the most delightful scene artifacts – Cobra Starship’s cover/reworking of Katy Perry’s I Kissed a Girl, appropriately retitled I Kissed a Boy. Despite being an emo bisexual who’s deeply enamored with the culture myself, the point of this piece is partially to remove the rose-tinted glasses some researchers and a lot of fans have regarding emo gender presentation and sexuality. Hence, I argue that the emo subculture constructed a very specific masculinist bisexuality, that ultimately remains focused on the hetero-centered male ideal.

Holy Shit, People Write Papers About This?: Literature Overview

As I said, surprisingly (or maybe unsurprisingly considering this very silly field I’m in) there’s actually a ton of reading to do analyzing emo, so I thought it would be beneficial to overview the general consensus before I give my own personal opinions. And if nothing else, jot those downs in your to-be-read lists because it’s a lot of fun.

The real MVP of doing research for this essay has been Judith Fathallah and her works Is Stage-Gay Queerbaiting? The Politics of Performative Homoeroticism in Emo Bands and Emo: How Fans Defined a Subculture. Really, her entire bibliography is delightful and everyone should check it out. The latter work in particular is a precious overview of all things emo, tracing its complicated history and cultural evolution. As it pertains to my subject, Fathallah paints a realistic picture of how both fans and artists constructed gender and sexuality. Between researchers who considered emo masculinity to be either nothing note-worthy or downright revolutionary, Fathallah errs on it being “reformist” (Emo, 22, Stage-Gay, 134). Emo repeatedly underlines that to fans, instances of homoeroticism were less threatening to its masculinist roots and perceived identity than “contamination” by femininity (Emo, 108). This sort of discourse is also band-sanctioned and perpetuated:

[F]eminine characteristics are devalued, even as the artists’ readiness to apply them to themselves simultaneously mitigates their stigma. Mocking feminine performativity while simultaneously professing enjoyment of that very quality carries over and is amplified in fan discourse on LiveJournal. (70)

She also remembers that Cobra Starship was a noteworthy player in the scene, exemplifying her MVP status. Here’s a quote that I will leave undiscussed for now, but do put a mental pin in it:

With regard to gender, [Victoria] Asher’s role was notable for its lack of note—she was a full participant in interviews and on stage, and the fact of her being a woman was scarcely mentioned. She dressed in a way that both signified femininity (skirts, long hair) and allotted her into the band as a group (matching color schemes, for instance). If Cobra Starship had actually been an emo band, her presence would have forestalled the objection that only men can be artists/instrumentals in emo. Despite sharing a label and frequent collaborations with emo bands, Cobra Starship was presented more as a commentary on emo than an emo band itself. (31)

Is Stage-Gay Queerbaiting? is much more specialized on its titular question, but still reinforces the point made in Emo. Fathallah discusses that it’s unproductive to question the ‘reality’ of the acts performed on stage by certain emo boys, but the outcome of those acts being tossed out into public discourse is much of the same: “[E]mo is rather more gender-radical for non-masculine boys than it is for girls of any description: ultimately, the subject-narrator is almost always male” (Stage-Gay, 133) and “Emo queerness serves queer boys a lot more directly than it does queer (or any) girls—which is not to say girls cannot re-appropriate its texts, in traditional fandom fashion, in a process which contributes to the queerness of the genre” (134). I really genuinely recommend this short and sweet paper to every RPF warrior in the trenches, a very interesting read.

The last work I read is Kaci Schmitt’s Exploring Dress and Behavior of the Emo Subculture and, to be honest, I’m quite hesitant to put this one on blast because it is literally just this poor woman’s Master’s thesis I dug up on the internet. But it does have very intriguing accounts from the source, so to speak, as she interviewed emo kids in the wild. Sorry and thank you for your work, Kaci.

The theme that is often echoed in Exploring Dress is that bisexuality is scoffed at as deeply performative by self-proclaimed emo kids. One of them, who’s gay himself, doesn’t even “believe in” bisexuality. People roll their eyes at the phenomenon of “emo boys kissing”, describing it as a purely online occurrence (Exploring Dress, 51), a cheap attempt at political radicality, and a strategy to attract girls (48). This is, while questioned, the most important and curious part of emo bisexuality. It is widely believed that homosexual male displays of affection (and they are nearly universally male) are in fact meant to attract the attention of heterosexual emo girls. There are reports featured from emo girls who admit to finding it hot (48), and even second-hand accounts of girls trying to coax guys into making out for their own pleasure/amusement (52).

This is a bit bananas to me, but I will highlight that this is pretty much the only instance of emo female sexuality explored by any of those works that can’t be classified under the, admittedly crude, category of ‘fangirling’, i.e. pining for band members. And it’s still goddamn dude-centered! It’s a sort of fun-house-mirror version of the usual male objectification of female bisexuality, poignantly described by Fathallah in her discussion of the Panic! at the Disco’s Girls/Girls/Boys video: “While the hypothetical bisexual woman holds all the cards in this scenario (“If you change your mind you know where I am”) it is ultimately only girl–girl relationships as framed and contained by the male gaze that are up for affirmation. In other words: look guys, hot lesbians” (Emo, 22). In any case, I will comment on it all more later down the road.

Seemingly everyone is in agreement over one thing: as far as emo experimented with gender and sexuality, it was with masculinity from a male perspective. Fandom spaces were often overrun with misogyny, thus women that participated in those fandoms either fell in line with masculinist narratives or risked the brand of ‘irrational boy-crazy fangirl’. Professional spaces suffered from misogyny even harder, with the only notable woman in the scene to this day being Paramore’s Hayley Williams3, and the women subjects of songs were often portrayed extremely unfavorably, especially in emo’s heyday in the early 2000s. As Jessica Hopper put in her essay Emo: Where the Girls Aren’t: “Emo was just another forum where women were locked in a stasis of outside observation, observing ourselves through the eyes of others.”

One thing I regret is not waiting/splurging for the release of Where Are Your Boys Tonight?: The Oral History of Emo's Mainstream Explosion 1999-2008 by Chris Payne. It just came out this year, and I’ve been seeing all kinds of jaw-dropping quotes floating around my Tumblr dashboard from it. Unfortunately, it always pains me to spend money “frivolously” and its newness ensures it’s not yet available through more illicit means4. It would be very useful, not to mention fun, to trace the same history and get the opinions about sexuality and gender straight from the horse’s mouth, but alas. All of this is to say that if you do have the money, get that book.

I Hope You Hang Yourself with Your H&M Scarf: Possible Origins of I Kissed a Boy

Sorry for the ungodly long preamble, but after discussing academic matters we must get real TMZ with it and discuss why the hell I Kissed a Boy by Cobra Starship is even a thing.

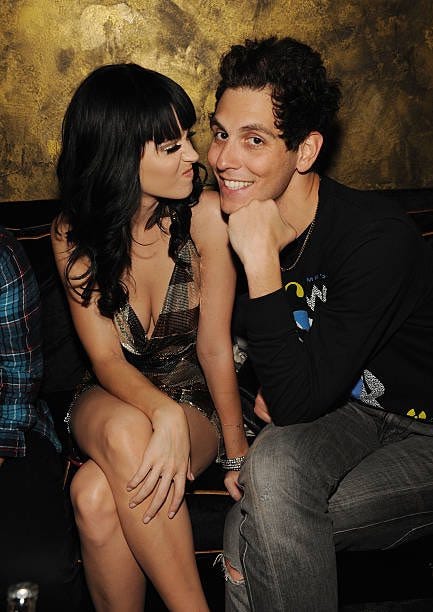

At this point a lot of this is ancient history, so it’s hard to prove anything past shady gossip, but I’ll allow myself a little speculation based on the scarce facts we know. Katy Perry, of feeling like a plastic bag fame, was once on roughly the same level of fame as the dudes in the scene, if you can believe it. She was seen hanging out with a bunch of them, sparking dating rumors about her and either Pete Wentz (of Fall Out Boy) or Travie McCoy (of Gym Class Heroes), as far as I can find. Travie and Gabe Saporta (of Cobra Starship) were both part of Pete’s label Decaydance, a subject very familiar to the readers of Unsafe Pin. The first rumor was not helped by the release of her 2007 song Ur So Gay and its accompanying music video, depicting a love interest very creatively named “Pierre Wertz”. Personally, I don’t buy that these two were ever involved romantically, seeing that Pete was still married to Ashlee Simpson, but it’s harder to deny that the song was for some reason designed to take the piss specifically out of him.

For one, the direct reference in Ur So Gay to the subject reading Hemingway is hard to interpret any way else when Wentz loved the author so much he literally owned a dog named after him. But more generally, the song just fits way too well into the general discourse around specifically Wentz’s sexuality, more so than any other notable emo boys at the time. The song mocks the subject’s gay presentation matched with his actual disinterest in a homosexual relationship in eerily the same way as the internet’s most captivating garbage fire Gawker (RIP) reacted to Wentz’s interview in Out Magazine:

He claims that he's sorta queer, but only "above the belt," because male "equipment" just doesn't do it for him. He doesn't even like his own cock! How zany, how hip, how fucking rock 'n roll. Except, you know, it's not at all because it's as put-on as his "so silly by now that he's almost doing a pastiche of himself" eyeliner.

Put that between “You don't eat meat and drive electrical cars” and ”You're so indie rock, it's almost an art” as a spoken word break and nobody would notice. To add insult to injury, the song catapulted Katy Perry to mega-fame, reaching #2 on Billboard’s Hot Singles Sales. I imagine seeing a cruel Ken-doll pastiche of yourself on MTV every other day isn’t exactly pleasant.

So it’s hardly surprising that next year a mocking cover of Katy Perry’s other gay-themed song appeared on Fall Out Boy’s CitizensFOB Mixtape: Welcome to the New Administration. Conceptually, I Kissed a Boy emits very strong “I got the kid in the divorce and now I’m gonna convince him mom is a bitch so he can tell that to everybody at school” vibes. As Fathallah wrote in her book, Cobra Starship existed sort of parallel to the emo and club scenes while actively making a mockery of them, so they are an absolutely great fit for a stunt like this, and the song fucking bangs.

You're Only Here for Our Amusement: The Song, Finally

This section will be organized as a loose comparison between the original and the cover specifically to demonstrate how both of them, while masquerading as songs about bisexuality, are really about straight dudes.

Plenty of ink has been spilled mocking and lamenting how stupid I Kissed a Girl is. I don’t think I have to explain to any slightly media-literate gay person what a pinnacle of ‘straight girl bi-curiosity’ it is, but I’ll give it a brief run anyway. Constant excusal and ‘extenuating circumstances’ (“I got so brave, drink in hand”) stigmatize expressions of same-sex attraction as something only done in a compromised state of mind. Simultaneously, lines like “Don’t mean I’m in love tonight” undermine that attraction as something unserious and temporary, something one can snap out of. Even Gabe Saporta, in his very own interview for Out Magazine, admits that “When [he] was growing up the acceptable homosexual ambiguity was girls making out with each other”. Most importantly, if the “I hope my boyfriend don’t mind it” doesn’t sum it up, the song describes a straight man’s fantasy of a bisexual woman - a hot, fetishized encounter after which she safely can return to him. “In other words: Look guys, hot lesbians”.

I Kissed a Boy on the other hand is not just a gender-inversed version of I Kissed a Girl, the entire sentiment of the song is flipped on its head. The narrator is not bashful or apologetic, he’s a dude who came to drink Jagerbombs and kick ass. And he’s all out of Jagerbombs. I found including this little chart instead of letting the reader look up the lyrics at their own discretion worthwhile because it’s really astounding how every line of each song looks like a yin and yang of weird bisexual posturing.

What is most striking is that in this song that was originally (at least supposedly) about same-sex attraction, it is really a non-presence. What takes the place of slightly fetishizing, but still attractive descriptors in the bridge is an outright threat. The same-sex encounter in I Kissed a Boy is not a sensual one, it’s an assault. A seemingly righteous one, challenging the “frat boy’s” homophobia and demonstrating the narrator’s secure masculinity, but still an assault. It curiously echoes Pete Wentz’s opinions on certain pockets of Fall Out Boy fans and how he handles them:

“A big portion of our fan base are these white-hat jock dudes who maybe actually have some kind of homoerotic behaviors, he says. They're so violent - but they feel pretty free at Fall Out Boy shows. So does he: It's all because I know I'm going to get a reaction - but it's all things that I believe anyway.” (This Charming Man)

And when discussing emo artists presenting as gay on stage, Judith Fathallah quotes Jane Ward:

“To the extent that sexual contact between straight white men is ever acknowledged, the cultural narratives that circulate around these practices typically suggest that they are not gay in their identitarian consequences, but are instead about building heterosexual men, strengthening hetero-masculine bonds, and strengthening the bonds of white manhood in particular . . . In particular, I am going to argue that when straight white men approach homosexual sex in the ‘right’ way—when they make a show of enduring it, imposing it, and repudiating it—doing so functions to bolster not only their heterosexuality, but also their masculinity and whiteness.” (Not Gay: Sex Between Straight White Men, quoted in Stage-Gay, 130)

Now, I won’t touch the inarguably significant aspect of race, but if I Kissed a Boy is not “a show of enduring it, imposing it, and repudiating it” then I frankly don’t know what is.

This demonstration of masculinity in the song is also made not solely for bonds between men, but for attracting women. What is important in Katy Perry’s kiss with a girl is that she liked it, what is important in Saporta’s is that “bitches loved it”. While this seems to fall in the category of the kind of awkward teenage “emo boys making out” Schmitt discusses in her thesis, it doesn’t. Instead, the song seems to consciously re-mold what this phenomenon entails: Where previously an emo guy making out with another guy would be a queer, even sometimes described as a degrading act committed for the female gaze, in I Kissed a Boy it is a conquest, a demonstration of superior masculinity. It cleanses queer implications from a queer act by just blasting it with Cobra Starship’s patented neon douchebag ray. A woman is not an actor with desire as was at least hinted at by the “emo boys making out” trope, she is once again the desirable object of tradition.

This is where I’m going to ask you to take out that mental pin from Fathallah’s quote regarding Victoria Asher and Cobra Starship. If you can’t tell already that I am quite deep in the trenches, I recently binged the entirety of CobraCam.TV, the band’s old-ass web show. Nothing to write home about there, but I did that after reading Fathallah’s Emo, so it jumped out at me that Asher was not, in fact, treated in a very feminist manner. Her gender was not very “lack of note”, and almost every time it came up the show found a way to make a sexualized joke out of it, even making a “hot lesbians” one when Asher and Leighton Meester were shown together during the Good Girls Go Bad video shoot.

I call this to attention for two reasons. First, this is not me #cancelling Cobra Starship, it’s me pointing out that it’s a little silly to look for heroes of feminism in a scene and culture where misogyny is ingrained to the core. Asher’s presence and treatment were not “notable”, they were quite typical. Even Fathallah acknowledges that Asher’s un-notability is likely due to Cobra’s existence on the margins of emo, as the culture of emo would not allow even that. Secondly, due to Cobra Starship’s entire schtick, it’s hard to distinguish between satire and genuine political belief with them. So, even if the wider impact of those jokes was negative, I’m absolutely not implying Asher was in any way mistreated. In fact, her participation in the CobraCam.TV skits points to those jokes just being off-color goofs between friends. This ambiguity of purpose also makes it difficult to say whether and to what degree I Kissed a Boy is meant to be taken seriously. Its above-discussed probable origins pull one way and Cobra Starship’s overarching criticism of the self-important club dude pulls another. In any case, I’m going to err on the side of misogyny and say it’s a better song than Katy Perry’s. #LoveLoses.

Wentzian Brand of Ambiguity: Emo and Gendered Bisexuality

I Kissed a Boy, as silly as it may be, does paint a pretty accurate picture of a very specific brand of emo bisexuality. A “Wentzian brand of ambiguity”, as Pete’s interviewer put it in Out Magazine. And it is a type of bisexuality that, to a variety of degrees, endlessly orbits maleness and straightness.

Maleness is an obvious one because women may as well be abstract concepts rather than conscious actors in the scene. When you’re collapsing under the general weight of misogyny, when there are practically no performers to represent you, when songs call you a heartless whore, and when you live in fear of the Sauron eye of dudes on the internet asking you to name five songs, there can be no meaningful talk of female bisexuality in emo as an equal concept to its male counterpart. The most proliferated and accessible thing we have is still Girls/Girls/Boys and that says enough. And in between men, even expressions of queerness are exhibited in tandem with denial of femininity: Fathallah notes how even in the wild, wild West of 4Chan “the conception of emo, then, actually has quite a lot of room for male queerness—much more than it has for women” (Emo, 129).

Straightness is less straightforward (ha), but it is nevertheless prolific. To recognize how central straight dudes are to emo expressions of bisexuality one just has to listen to what the biggest names were saying: Gerard Way told Spin Magazine “I didn’t want the girls to want to fuck me, I wanted the straight guys to want to fuck me”, Gabe Saporta taunted a homophobic heckler at a show with “Why don't you bend over?”, and Pete Wentz’s Out interviewer described how “The more uncomfortable or conservative his audience, the less likely he is to give them an easy out.” It is, as many cynical onlookers suspect, often less about expressing authentic selfhood and more about challenging bigots. Again, this is not to discredit the effort these bands put in to enact social and political change but to point this out to people who still believe ‘emo bisexuality’ was a genuine expression of sexual preference instead of performing a political statement. It’s also very straight in that, as discussed above, heterosexual desire is the point of bisexual posturing, but despite its appearance in I Kissed a Boy, I would argue this is an aspect largely of just the fan communities.

Emo bisexuality as it existed historically is like one of the Scooby Doo monsters. You think it’s a groundbreaking, queer statement, a cultural anomaly, then you pull the mask off and it’s just usual cis-straight guy nonsense.

Not all hope is lost though. As the emo renaissance is now well underway, I think it is reasonable to assume the trends within it are going to stick with the subculture. As Fathallah discusses in Is Stage-Gay Queerbaiting?, the legendary stage-gay incidents of old issued “a kind of license or authorization to queer fan practice, resulting in a freer space of play” (128) and I would argue this practice cemented and persisted into the new age of emo. So, even if there was a shoddy start, with strides in women’s and queer rights and with the efforts of fans, what I’m observing is that emo bisexuality is getting actively de-gendered.

I’d say this is largely due to the enhancement of trans voices in the fandom. It seems that a lot of the emo “boys” making out and the “girls” finding it hot found a thing or two out about themselves. “You should’ve raised a baby girl / I should’ve been a better son” and whatnot. And so, when the barriers of gender are broken down, so are the ones of gendered attraction. It becomes a little silly to differentiate between male and female bisexuality when bisexuality encompasses the entirety of the vast gender spectrum. There’s a unique connection and interchange between emo performers and the fan communities, so you can also see this sentiment reflected in performance: Gerard Way, who long identified as nonbinary, started regularly appearing in elaborate dresses and skirts, and Pete Wentz just grew out his hair and dons a kilt from time to time with no special fanfare. There’s less direct endorsement for the community and definitely less stage-gay5, but I would say that has only done well by unanchoring bisexuality from these (still almost exclusively male) performers’ point of view. Everybody definitely outgrew making fun of girls in fan forums and in songs with no criticism, so even if the scene is still very male, the tide is slowly but surely turning.

That does, sadly (for me at least), mean that we will probably not get anything like I Kissed a Boy or Pete Wentz calling himself a fag or Jon Walker, bassist of Panic! at the Disco, signing out with “Jon Walker is a boy” again. But as the emo renaissance only gains steam, even if the genre is reformist rather than radical, I’m excited to see what kind of batshit queer weirdness we’ll get when the pendulum swings in a better direction.

I would also argue this applies to the larger pop-punk fandom, maybe even branching off into some hardcore circles, but that is less documented (and thus provable) and for simplicity’s sake I stick with the umbrella of “emo”. But in my heart of hearts, I know Slipknot fans know each other carnally.

You can pull out any indie emo band involving women you want to argue with me on this point, but we are not talking about small indie bands. Paramore is the only one in the same ballpark as giants like My Chemical Romance or Fall Out Boy. The only exception (lol) other than her I will accept is Victoria Asher, but Cobra Starship is long inactive and that would only bring the total to the staggering number of two.

Well, I guess that depends. Use how you characterize Mikey Way appearing on Fall Out Boy’s So Much (for) Tourdust as a litmus test.